Seniors who were born after 1931are less likely to sell their homes than were previous generations—and it’s a significant cause of the housing shortage, according to the “February Insight” report from Freddie Mac.

The result is around 1.6 million houses weren’t for sale through 2018, representing about one year’s supply of new construction, or more than 50 percent of the shortfall of 2.5 million housing units—that the market faces. The scarcity factor serves to increase housing prices and make renting more attractive to younger generations. However, a shortfall of new construction increases house prices and rental rates.

“We believe the additional demand for homeownership from seniors aging in place will increase the relative price of owning versus renting, making renting more attractive to younger generations,” said Sam Khater, chief economist at Freddie Mac. “This further highlights the importance of addressing barriers to the production of new housing supply to help accommodate long-term housing demand.”

Improved health and higher levels of education are causes of the trend. And it’s likely to increase over time as improvements in health care and technology make aging in place easier. For example, the capability to Skype with a doctor.

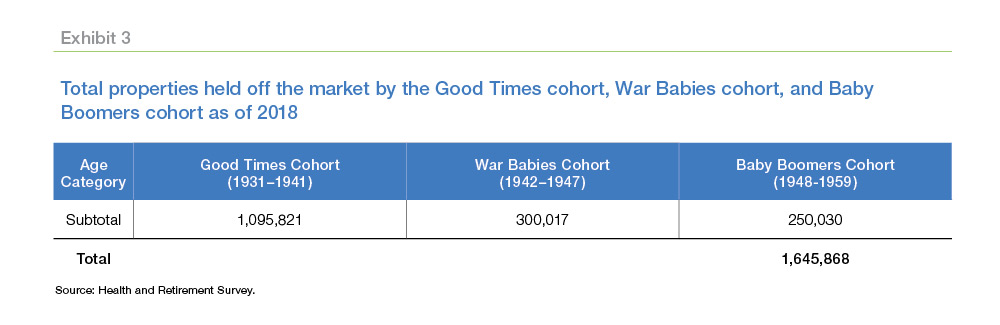

Exhibit 1 displays the homeownership rates for seniors aged 67 to 85 for two cohorts. The first is the “Good Times” cohort, who were born during the bad times between 1931 and 1941, though they have received the advantages of good times through their lifetime.

The second cohort includes the previous generations for which data are available in the Health and Retirement Survey as of 2014: Those born before 1924 and the “children of the Depression” born between 1924 and 1930.

The second cohort includes the previous generations for which data are available in the Health and Retirement Survey as of 2014: Those born before 1924 and the “children of the Depression” born between 1924 and 1930.

There are significant differences in these two groups in the age in which households cease being homeowners. Starting right after age 67, Good Times households stay in their homes at higher rates. Between the ages of 67 and 82, while the homeownership rate had dropped by 11.6 percent for previous generations, it fell by only 3.6 percent for the Good Times cohort.

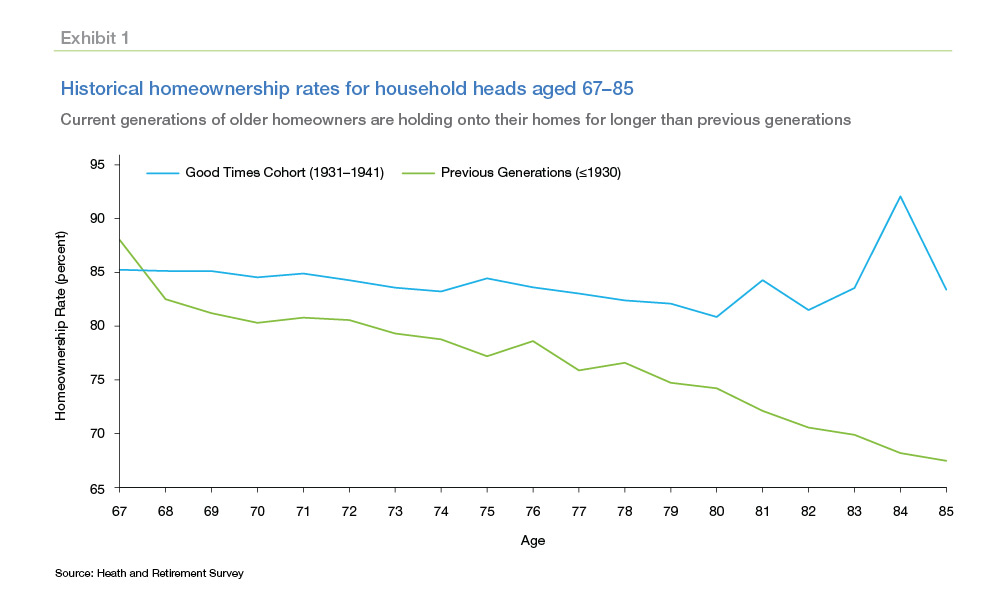

As shown in Exhibit 2, even at ages 81 to 85, the homeownership rates for the Good Times cohort are still above 80 percent. By contrast, homeownership rates fell to 71 percent for previous generations. The homeownership gap between the two groups swells to 15 percent at ages 81 to 85.

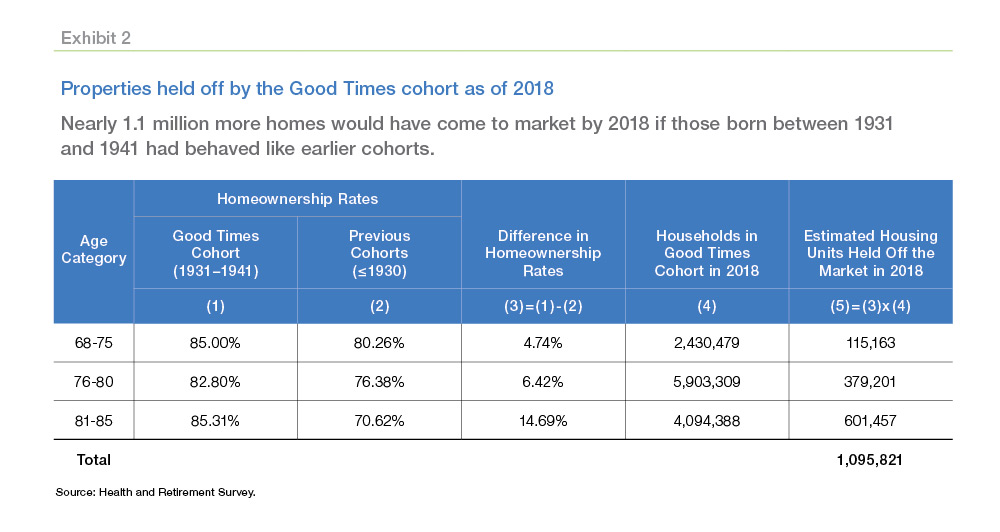

In addition to the Good Times cohort, later cohorts such as War Babies, 1942–1947; as well as Baby Boomers, 1948–1959, are expected to stay in their homes at higher rates, and increase the number of houses held off the market.

In addition to the Good Times cohort, later cohorts such as War Babies, 1942–1947; as well as Baby Boomers, 1948–1959, are expected to stay in their homes at higher rates, and increase the number of houses held off the market.

Freddie made a similar calculation for the War Babies and Baby Boomers and estimates that an additional 550,000 homes were held off the market by these cohorts by 2018, as shown in Exhibit 3.

Freddie estimates there were around 1.6 million housing units held off the market by those three cohorts as of 2018. This amounts to 2.1 percent of owner-occupied housing units in the U.S. as of 2018. The seniors that transition from homeownership to renting would free up more owner-occupied housing units, but also would increase demand for rental units. Also, the higher propensity of homeownership would not lead to shortages in markets with elastic supply because shortfalls would be offset by an increase in housing stock.

Despite the weakening of the housing market in 2018, early 2019 data signals a possible turnaround for the year to come. This recent uptick in activity proves that homebuyers are very sensitive to changing rates and will likely respond positively if mortgage rates remain low.

After steadily increasing for years, home prices have finally begun to cool, and while they're still increasing, Freddie Mac expects the rate of growth to slow. The growth rate of the Freddie Mac House Price Index, for instance, fell slightly to 0.7 percent in the fourth quarter of 2018. It forecasts home prices will increase 4.1 percent in 2019 and 2.7 percent in 2020.

The most important fundamental in today's housing market is the lack of houses for sale. This shortage has been identified as an important barrier to young adults buying their first homes.

Older Americans prefer to age in place because they are satisfied with their communities, their homes, and their quality of life, according to Freddie Mac. The result is more senior households are staying in place than would have been the case--if they behaved like older generations of homeowners.

The number of homes retained by seniors is likely to grow as both the number of seniors increases and the barriers to staying in place are reduced. Removing barriers that can prevent the production of new housing supply is key if housing supply can meet the demand from borrowers in the future.